IMF View of World Economy and Finance, “Let’s Twist Again” Monetary Policy Worsening World Financial Turbulence and Global Growth Standstill

Carlos M. Pelaez

© Carlos M. Pelaez, 2010, 2011

Executive Summary

I IMF View of World Economy and Finance

IA Outlook of World Economy and Finance

IB Global Rebalancing

II World Financial Turbulence

IIA Collapse of Valuations of Risk Financial Assets

IIA1 Euro Zone Survival Risk

IIB Markets Not Dancing Twist

III Global Inflation

IV World Economic Slowdown

IVA United States

IVB Japan

IVC China

IVD Euro Area

IVE Germany

IVF France

IVG Italy

IVH United Kingdom

V Valuation of Risk Financial Assets

VI Economic Indicators

VII Interest Rates

VIII Conclusion

References

Executive Summary

The term “operation twist” grew out of the dance “twist” popularized by successful musical performer Chubby Chekker (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aWaJ0s0-E1o). The crucial issue in “twisting time” monetary policy is if lowering the yields of long-term Treasury securities would have any impact on investment and consumption or aggregate demand. The decline of long-term yields of Treasury securities would have to cause decline of yields of asset-backed securities used to securitize loans for investment by firms and purchase of durable goods by consumers. The decline in costs of investment and consumption of durable goods would ultimately have to result in higher investment and consumption. It is possible that the decline in yields captured by event studies is ephemeral. The decline in yields just after “let’s twist again” monetary policy this week was caused by the flight out of risk financial assets into Treasury securities, which is the opposite of the desired effect of encouraging risk-taking in asset-backed securities and lending.

There is a new carry trade that learned from the losses after the crisis of 2007 or learned from the crisis how to avoid losses. The sharp rise in valuations of risk financial assets shown in Table 37 in the text after the first policy round of near zero fed funds and quantitative easing by the equivalent of withdrawing supply with the suspension of the 30-year Treasury auction was on a smooth trend with relatively subdued fluctuations. The credit crisis and global recession have been followed by significant fluctuations originating in sovereign risk issues in Europe, doubts of continuing high growth and accelerating inflation in China, events such as in the Middle East and Japan and insufficient growth, falling real wages, depressed hiring and high job stress of unemployment and underemployment in the US now with realization of growth standstill recession.

The “trend is your friend” motto of traders has been replaced with a “hit and realize profit” approach of managing positions to realize profits without sitting on positions. There is a trend of valuation of risk financial assets driven by the carry trade from zero interest rates with fluctuations provoked by events of risk aversion. Table 40, which is updated for every comment of this blog and is anticipated here from the text, shows the deep contraction of valuations of risk financial assets after the Apr 2010 sovereign risk issues in the fourth column “∆% to Trough.” There was sharp recovery after around Jul 2010 in the last column “∆% Trough to 09/23/11,” which has been recently stalling or reversing amidst profound risk aversion. “Let’s twist again” monetary policy during the week of Sep 23 caused deep worldwide risk aversion and selloff of risk financial assets. Monetary policy was designed to increase risk appetite but instead suffocated risk exposures. Recovering risk financial assets in column “∆% Trough to 09/23/11” are in the range from 0.8 percent for the Shanghai Composite and 15.4 percent for the DJ UBS Commodity Index. The carry trade from zero interest rates to leveraged positions in risk financial assets has proved strongest for commodity exposures. Before the current round of risk aversion, all assets in the column “∆% Trough to 09/23/11” had double digit gains relative to the trough around Jul 2, 2010. There are now several valuations lower than those at the trough around Jul 2: European stocks index STOXX 50 is now 5.8 percent below the trough on Jul 2, 2010; the NYSE Financial Index is 11.7 percent below the trough on Jul 2, 2010; Germany’s DAX index is 8.4 percent below; and Japan’s Nikkei Average is 2.9 below the trough on Aug 31, 2010 and 24.9 percent below the peak on Apr 5, 2010. The Nikkei Average closed at 8560.25 on Fri Sep 23, which is 16.5 percent below 10,254.43 on Mar 11 on the date of the earthquake. Global risk aversion erased the earlier gains of the Nikkei. The dollar depreciated by 13.3 percent relative to the euro and even higher before the new bout of sovereign risk issues in Europe. The column “∆% week to 09/23/2011” shows sharp losses for all risk financial assets in Table 40. The realization that there were no more remedies of monetary policy for the global economic slowdown caused flight away from exposures in risk financial assets. There are still high uncertainties on European sovereign risks, US and world growth recession and China’s growth and inflation tradeoff. Sovereign problems in the “periphery” of Europe and fears of slower growth in Asia and the US cause risk aversion with trading caution instead of more aggressive risk exposures. There is a fundamental change in Table 40 from the relatively upward trend with oscillations since the sovereign risk event of Apr-Jul 2010. Performance is best assessed in the column “∆% Peak to 9/23/11” that provides the percentage change from the peak in Apr 2010 before the sovereign risk event to Jul 29. Most financial risk assets had gained not only relative to the trough as shown in column “∆% Trough to 9/23/11” but also relative to the peak in column “∆% Peak to 9/23/11.” There are now no indexes above the peak, not even the DJ UBS Commodity Index that is 1.3 percent below the peak. There are several indexes well below the peak: NYSE Financial Index (http://www.nyse.com/about/listed/nykid.shtml) by 29.7 percent, Nikkei Average by 24.9 percent, Shanghai Composite by 24.7 percent, STOXX 50 by 24.4 percent and Dow Global by 18.4 percent. S&P 500 is lower relative to the peak by 6.5 percent, DJ Asia Pacific is lower by 11.8 percent and the DJIA is lower by 6.4 percent. The factors of risk aversion have adversely affected the performance of risk financial assets. The performance relative to the peak in Apr is more important than the performance relative to the trough around early Jul because improvement could signal that conditions have returned to normal levels before European sovereign doubts in Apr 2010. The situation of risk financial assets has worsened.

Table 40, Stock Indexes, Commodities, Dollar and 10-Year Treasury

| Peak | Trough | ∆% to Trough | ∆% Peak to 9/ 23/11 | ∆% Week 9/ | ∆% Trough to 9/ | |

| DJIA | 4/26/ | 7/2/10 | -13.6 | -3.9 | -6.4 | 11.2 |

| S&P 500 | 4/23/ | 7/20/ | -16.0 | -6.6 | -6.5 | 11.1 |

| NYSE Finance | 4/15/ | 7/2/10 | -20.3 | -29.7 | -8.6 | -11.7 |

| Dow Global | 4/15/ | 7/2/10 | -18.4 | -18.5 | -7.6 | -0.2 |

| Asia Pacific | 4/15/ | 7/2/10 | -12.5 | -11.8 | -7.0 | 0.8 |

| Japan Nikkei Aver. | 4/05/ | 8/31/ | -22.5 | -24.9 | -3.4 | -2.9 |

| China Shang. | 4/15/ | 7/02 | -24.7 | -23.1 | -1.9 | 2.1 |

| STOXX 50 | 4/15/10 | 7/2/10 | -15.3 | -24.4 | -5.2 | -10.7 |

| DAX | 4/26/ | 5/25/ | -10.5 | -17.9 | -6.8 | -8.4 |

| Dollar | 11/25 2009 | 6/7 | 21.2 | 10.8 | 2.1 | -13.3 |

| DJ UBS Comm. | 1/6/ | 7/2/10 | -14.5 | -1.3 | -9.1 | 15.4 |

| 10-Year Tre. | 4/5/ | 4/6/10 | 3.986 | 1.825 |

T: trough; Dollar: positive sign appreciation relative to euro (less dollars paid per euro), negative sign depreciation relative to euro (more dollars paid per euro)

Source: http://professional.wsj.com/mdc/page/marketsdata.html?mod=WSJ_hps_marketdata

I IMF View of World Economy and Finance. The International Financial Institutions (IFI) consists of the International Monetary Fund, World Bank Group, Bank for International Settlements (BIS) and the multilateral development banks, which are the European Investment Bank, Inter-American Development Bank and the Asian Development Bank (Pelaez and Pelaez, International Financial Architecture (2005), The Global Recession Risk (2007), 8-19, 218-29, Globalization and the State, Vol. II (2008b), 114-48, Government Intervention in Globalization (2008c), 145-54). There are four types of contributions of the IFIs:

1. Safety Net. The IFIs contribute to crisis prevention and crisis resolution.

i. Crisis Prevention. An important form of contributing to crisis prevention is by surveillance of the world economy and finance by regions and individual countries. The IMF and World Bank conduct periodic regional and country evaluations and recommendations in consultations with member countries and also jointly with other international organizations. The IMF and the World Bank have been providing the Financial Sector Assessment Program (FSAP) by monitoring financial risks in member countries that can serve to mitigate them before they can become financial crises

ii. Crisis Resolution. The IMF jointly with other IFIs provides assistance to countries in resolution of those crises that do occur. Currently, the IMF is cooperating with the government of Greece, European Union and European Central Bank in resolving the debt difficulties of Greece as it has done in the past in numerous other circumstances

2. Surveillance. The IMF conducts surveillance of the world economy, finance and public finance with continuous research and analysis. Important documents of this effort are the World Economic Outlook of which the current one is IMF (2011WEOSep), Global Financial Stability Report of which the current one is IMF (2011GFSRSep) and Fiscal Monitor of which the current one is IMF (2011FMSep)

3. Infrastructure and Development. The IFIs also engage in infrastructure and development, in particular the World Bank Group and the multilateral development banks

4. Soft Law. Significant activity by IFIs has engaged in developing standards and codes under multiple forums. It is easier and faster to negotiate international agreements under soft law that are not binding but can be very effective. These norms and standards can solidify world economic and financial arrangements

The objective of this section is to analyze the current view of the IMF on the world economy (IMF 2011WEOSep), international finance (IMF2011GFSRSep) and global fiscal affairs (IMF2011FMSep). Subsection IA Outlook of World Economy and Finance probes the rich database of the IMF (WEO2011WEOSep http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2011/02/weodata/index.aspx) and subsection IB Global Rebalancing considers the analysis of the world economy and finance by the IMF.

IA Outlook of World Economy and Finance. Table 1 is constructed with the database of the IMF (http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2011/02/weodata/index.aspx) to show GDP in dollars in 2010 and the growth rate of real GDP of the world and selected regional countries from 2011 to 2014. The data illustrate the concept often repeated of “two-speed recovery” of the world economy from the recession of 2007 to 2009. The IMF has lowered its forecast of the world economy to 3.9 percent in 2011 and 3.9 percent in 2012 but accelerating to 4.5 percent in 2013 and 4.7 percent in 2014. Slow-speed recovery occurs in the “major advanced economies” of the G7 that account for $31,717 billion of world output of $62,911 billion but are projected to grow at much lower rates than world output, 1.9 percent on average from 2011 to 2014 in contrast with 4.3 percent for the world as a whole. While the world would cumulatively grow 18.1 percent in the four years from 2011 to 2014, the G7 as a whole would cumulatively grow 7.9 percent. The difference in dollars of 2010 is rather high: growing by 18.1 percent would add $11.4 trillion of output to the world economy, or roughly two times the output of the economy of Japan of $5,459 but growing by 7.9 percent would add $4.9 trillion of output to the world, or somewhat less than the output of Japan in 2010. The “two speed” concept is in reference to the growth of the 150 countries labeled as emerging and developing economies (EMDE) with joint output in 2010 of $21,536 billion, or 34.2 percent of world output. The EMDEs would grow cumulatively 28.2 percent or at the average yearly rate of 6.4 percent, contributing $6.0 trillion from 2011 to 2014 or the equivalent of almost the GDP of $5,878 billion of China in 2010. The final four countries in Table 1 (Brazil, Russia, India and China) are large, rapidly growing emerging economies. Their combined output adds to $11,808 billion, or 17.6 percent of world output, which is equivalent to 24.9 percent of the major advanced economies of the G7.

Table 1, IMF World Economic Outlook Database Projections of Real GDP Growth

| GDP USD 2010 | Real GDP ∆% 2011 | Real GDP ∆% 2012 | Real GDP ∆% 2013 | Real GDP ∆% 2014 | |

| World | 62,911 | 3.9 | 3.9 | 4.5 | 4.7 |

| G7 | 31,717 | 1.3 | 1.7 | 2.2 | 2.5 |

| Canada | 1,577 | 2.1 | 1.9 | 2.5 | 2.5 |

| France | 2,563 | 1.7 | 1.4 | 1.9 | 2.1 |

| DE | 3,286 | 2.7 | 1.3 | 1.5 | 1.5 |

| Italy | 2,055 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.8 |

| Japan | 5,459 | -0.5 | 2.3 | 2.0 | 1.9 |

| UK | 2,250 | 1.1 | 1.6 | 2.3 | 2.6 |

| US | 14,527 | 1.5 | 1.8 | 2.5 | 3.1 |

| Euro Area | 12,168 | 1.6 | 1.1 | 1.5 | 1.7 |

| DE | 3,286 | 2.7 | 1.3 | 1.5 | 1.5 |

| France | 2,563 | 1.7 | 1.4 | 1.9 | 2.1 |

| Italy | 2,055 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.8 |

| POT | 229 | -2.2 | -1.8 | 1.2 | 2.5 |

| Ireland | 207 | 0.4 | 1.5 | 2.2 | 2.8 |

| Greece | 305 | -5.0 | -2.0 | 1.5 | 2.3 |

| Spain | 1,410 | 0.8 | 1.1 | 1.8 | 1.9 |

| EMDE | 21,536 | 6.4 | 6.1 | 6.5 | 6.6 |

| Brazil | 2,090 | 3.8 | 3.6 | 4.2 | 4.2 |

| Russia | 1,480 | 4.3 | 4.1 | 4.1 | 4.0 |

| India | 1,632 | 7.8 | 7.5 | 8.1 | 8.1 |

| China | 5,878 | 9.5 | 9.0 | 9.5 | 9.5 |

Notes; DE: Germany; EMDE: Emerging and Developing Economies (150 countries)

Source: IMF World Economic Outlook databank http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2011/02/weodata/index.aspx

Continuing high rates of unemployment in advanced economies constitute another characteristic of the database of the WEO (http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2011/02/weodata/index.aspx). Table 2 is constructed with the WEO database to provide rates of unemployment from 2010 to 2014 for major countries and regions. In fact, unemployment rates in Table 2 are high for all countries: unusually high for countries with high rates most of the time and unusually high for countries with low rates most of the time. The rates of unemployment are particularly high for the countries with sovereign debt difficulties in Europe: 12.0 percent for Portugal (POT), 13.6 percent for Ireland, 12.5 percent for Greece, 20.1 percent for Spain and 8.4 percent for Italy, which is lower but still high. The G7 rate of unemployment is 8.2 percent. Unemployment rates are not likely to decrease substantially if slow growth persists in advanced economies.

Table 2, IMF World Economic Outlook Database Projections of Unemployment Rate as Percent of Labor Force

| % Labor Force 2010 | % Labor Force 2011 | % Labor Force 2012 | % Labor Force 2013 | % Labor Force 2014 | |

| World | |||||

| G7 | 8.2 | 7.8 | 7.7 | 7.5 | 7.0 |

| Canada | 7.9 | 7.6 | 7.7 | 7.2 | 6.6 |

| France | 9.8 | 9.5 | 9.2 | 8.9 | 8.6 |

| DE | 7.1 | 6.0 | 6.2 | 6.4 | 6.3 |

| Italy | 8.4 | 8.2 | 8.5 | 8.6 | 8.3 |

| Japan | 5.1 | 4.9 | 4.8 | 4.6 | 4.4 |

| UK | 7.9 | 7.8 | 7.8 | 7.8 | 7.4 |

| US | 9.6 | 9.1 | 9.0 | 8.5 | 7.8 |

| Euro Area | 10.1 | 9.9 | 9.9 | 9.7 | 9.3 |

| DE | 7.1 | 6.0 | 6.2 | 6.4 | 6.3 |

| France | 9.8 | 9.5 | 9.2 | 8.9 | 8.6 |

| Italy | 8.4 | 8.2 | 8.5 | 8.6 | 8.3 |

| POT | 12.0 | 12.2 | 13.4 | 13.4 | 12.4 |

| Ireland | 13.6 | 14.3 | 13.9 | 13.2 | 12.4 |

| Greece | 12.5 | 16.5 | 18.5 | 18.9 | 18.5 |

| Spain | 20.1 | 20.7 | 19.7 | 18.5 | 17.5 |

| EMDE | |||||

| Brazil | 6.7 | 6.7 | 7.5 | 7.0 | 7.0 |

| Russia | 7.5 | 7.3 | 7.1 | 7.0 | 7.0 |

| India | |||||

| China | 4.1 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 |

Notes; DE: Germany; EMDE: Emerging and Developing Economies (150 countries)

Source: IMF World Economic Outlook databank http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2011/02/weodata/index.aspx

Newly released data by the US Census Bureau on income, poverty and health insurance (DeNavas-Walt, Proctor and Smith 2011) and the flow of funds report of the Federal Reserve System for IIQ2011 (http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/z1/Current/z1.pdf) are summarized in Table 3. These reports depict 2010 household income of the US in constant 2010 dollars regressing to the level of 1996 and wealth of households and nonprofit organizations of the US in IIQ2011 falling $5.8 trillion below the level of 2007. The number of people in poverty in the US in 2010 is 46.180 million, equivalent to 15.1 percent of the population, which is the same as in 1993 and higher or equal than any percentage since 17.3 percent in 1965. The number of people without health insurance in 2010 is 49.904 million, which is 16.3 percent of the population. Although the economy recovered throughout 2010, income, wealth, poverty and lack of health insurance deteriorated. Increasing poverty and lack of health insurance suggest strengthening the social and health safety net. Evidence provided in prior blogs (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/09/collapse-of-household-income-and-wealth.html) shows that part of the explanation of the dramatically poor socio-economic indicators of the US could be explained by the sharp economic contraction from IV2007 to IIQ2009 but part originates in the worst recovery in a cyclical expansion during the postwar period.

Table 3, Summary of Social and Economic Indicators

| People in Poverty | 46.180 million |

| People without Health Insurance | 49.985 million |

| Median Household Income | $49,445 |

| People in Job Stress | 29.9 million unemployed or underemployed |

| Household Loss of Net Worth | -$5.8 trillion since 2007 |

| Household Loss of Real Estate | -$5.1 trillion since 2007 |

| Household Loss of Assets | -$6.3 trillion since 2007 |

Sources: DeNavas-Walt, Proctor and Smith (2011)

http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/z1/Current/z1.pdf

Bureau of Labor Statistics

The database of the WEO (http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2011/02/weodata/index.aspx) is used to construct the debt/GDP ratios of regions and countries in Table 4. The concept used is general government debt, which consists of central government debt, such as Treasury debt in the US, and all state and municipal debt. Net debt is provided for all countries except for gross debt for China, Russia and India. The net debt/GDP ratio of the G7 jumps from 76.5 in 2010 to 91.2 in 2014. G7 debt is pulled by the high debt of Japan that grows from 117.2 percent of GDP in 2010 to 152.8 percent of GDP in 2014. US general government debt grows from 68.3 percent of GDP in 2010 to 84.6 percent of GDP in 2014. Debt/GDP ratios of countries with sovereign debt difficulties in Europe are particularly worrisome. General government net debts of Italy, Ireland, Greece and Portugal exceed 100 percent of GDP or are expected to exceed 100 percent of GDP by 2014. The only country with relatively low debt/GDP ratio is Spain with 48.7 in 2010 but growing to 63.4 in 2014. Fiscal adjustment, voluntary or forced by defaults, may squeeze further economic growth and employment in many countries. Defaults could feed through exposures of banks and investors to financial institutions and economies in countries with sounder fiscal affairs.

Table 4, IMF World Economic Outlook Database Projections, General Government Net Debt as Percent of GDP

| % Debt/ GDP 2010 | % Debt/ GDP 2011 | % Debt/ GDP 2012 | % Debt/ GDP 2013 | % Debt/ GDP 2014 | |

| World | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| G7 | 76.5 | 81.6 | 86.3 | 89.3 | 91.2 |

| Canada | 32.2 | 34.9 | 36.8 | 37.1 | 36.5 |

| France | 76.5 | 80.9 | 83.5 | 84.9 | 84.9 |

| DE | 57.6 | 57.2 | 56.9 | 56.6 | 55.3 |

| Italy | 99.4 | 100.4 | 100.7 | 99.6 | 98.4 |

| Japan | 117.2 | 130.6 | 138.9 | 146.4 | 152.8 |

| UK | 67.7 | 72.9 | 76.9 | 78.1 | 77.2 |

| US | 68.3 | 72.6 | 78.4 | 82.2 | 84.6 |

| Euro Area | 65.9 | 68.6 | 70.1 | 70.6 | 70.0 |

| DE | 57.6 | 57.2 | 56.9 | 56.6 | 55.3 |

| France | 76.5 | 80.9 | 83.5 | 84.9 | 84.2 |

| Italy | 99.4 | 100.4 | 100.7 | 99.6 | 98.4 |

| POT | 88.7 | 101.8 | 107.6 | 110.7 | 110.4 |

| Ireland | 78.0 | 98.8 | 104.6 | 107.4 | 105.7 |

| Greece | 142.8 | 153.1 | 175.4 | 173.6 | 163.6 |

| Spain | 48.7 | 56.0 | 58.7 | 61.3 | 63.4 |

| EMDE | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Brazil | 40.2 | 38.6 | 37.5 | 36.4 | 35.2 |

| Russia* | 11.7 | 11.7 | 12.1 | 12.6 | 14.5 |

| India* | 64.1 | 62.4 | 61.9 | 60.9 | 60.5 |

| China* | 33.8 | 26.9 | 22.2 | 18.5 | 15.5 |

Notes; DE: Germany; EMDE: Emerging and Developing Economies (150 countries)

Source: IMF World Economic Outlook databank http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2011/02/weodata/index.aspx

The primary balance consists of revenues less expenditures but excluding interest revenues and interest payments. It measures the capacity of a country to generate sufficient current revenue to meet current expenditures. Brazil is the only country in Table 5 with surplus of primary net lending/borrowing in 2010. Germany has a small primary net/lending deficit of 0.3 percent in 2010 but moves into surplus after 2011, which is also the case of Italy with deficit of 0.3 percent in 2010 but projected surpluses after 2011. Most countries in Table 5 face significant fiscal adjustment in the future.

Table 5, IMF World Economic Outlook Database Projections of Primary General Government Net Lending/Borrowing as Percent of GDP

| % GDP 2010 | % GDP 2011 | % GDP 2012 | % GDP 2013 | % GDP 2014 | |

| World | |||||

| G7 | -6.5 | -5.9 | -4.5 | -3.1 | -2.2 |

| Canada | -4.9 | -3.7 | -2.5 | -1.4 | -0.5 |

| France | -4.9 | -3.4 | -2.1 | -1.4 | -0.4 |

| DE | -1.2 | 0.4 | 0.8 | 1.2 | 1.9 |

| Italy | -0.3 | 0.5 | 2.6 | 4.1 | 4.5 |

| Japan | -8.1 | -8.9 | -7.7 | -6.2 | -5.6 |

| UK | -7.7 | -5.6 | -4.1 | -2.2 | -0.7 |

| US | -8.4 | -7.9 | -6.3 | -4.6 | -3.4 |

| Euro Area | -3.6 | -1.5 | -0.3 | 0.5 | 1.2 |

| DE | -1.2 | 0.4 | 0.8 | 1.2 | 1.9 |

| France | -4.9 | -3.4 | -2.1 | -1.4 | -0.4 |

| Italy | -0.3 | 0.5 | 2.6 | 4.1 | 4.5 |

| POT | -6.3 | -1.9 | 0.1 | 1.9 | 2.6 |

| Ireland | -28.9 | -6.8 | -4.4 | -1.5 | 1.3 |

| Greece | -4.9 | -1.3 | 0.8 | 3.3 | 5.7 |

| Spain | -7.8 | -4.4 | -3.1 | -2.1 | -1.4 |

| EMDE | |||||

| Brazil | 2.4 | 3.2 | 3.0 | 2.9 | 2.9 |

| Russia | -3.2 | -0.6 | -1.3 | -1.4 | -2.4 |

| India* | -8.4 | -7.7 | -7.3 | -7.2 | -7.1 |

| China* | -2.3 | -1.6 | -0.8 | -0.1 | 0.0 |

*General Government Net Lending/Borrowing

Notes; DE: Germany; EMDE: Emerging and Developing Economies (150 countries)

Source: IMF World Economic Outlook databank http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2011/02/weodata/index.aspx

There were some hopes that the sharp contraction of output during the global recession would eliminate current account imbalances. Table 6 constructed with the database of the WEO (http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2011/02/weodata/index.aspx) shows that external imbalances have been maintained in the form of current account deficits and surpluses. China’s current account surplus is 5.2 percent of GDP for 2010 and is projected to climb to 6.7 percent of GDP in 2014. At the same time the current account deficit of the US is 3.2 percent of GDP and is projected to decline to 1.8 percent of GDP in 2014. The current account surplus of Germany is 5.7 percent for 2010 and remains at a high 4.7 percent of GDP in 2014. Japan’s current account surplus is 3.6 percent of GDP in 2010 and declines slightly to 2.6 percent of GDP in 2014. These imbalances are analyzed in the following subsection.

Table 6, IMF World Economic Outlook Databank Projections, Current Account of Balance of Payments as Percent of GDP

| % CA/ GDP 2010 | % CA/ GDP 2011 | % CA/ GDP 2012 | % CA/ GDP 2013 | % CA/ GDP 2014 | |

| World | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 |

| G7 | -1.0 | -1.2 | -0.7 | -0.5 | -0.5 |

| Canada | -3.1 | -3.3 | -3.8 | -3.5 | -3.2 |

| France | -1.7 | -2.7 | -2.5 | -2.5 | -2.6 |

| DE | 5.7 | 5.0 | 4.9 | 4.8 | 4.7 |

| Italy | -3.3 | -3.5 | -2.9 | -2.5 | -2.3 |

| Japan | 3.6 | 2.5 | 2.8 | 2.6 | 2.6 |

| UK | -3.2 | -2.7 | -2.3 | -1.7 | -1.1 |

| US | -3.2 | -3.1 | -2.1 | -1.7 | -1.8 |

| Euro Area | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| DE | 5.7 | 5.0 | 4.9 | 4.8 | 4.7 |

| France | -1.7 | -2.7 | -2.5 | -2.5 | -2.6 |

| Italy | -3.3 | -3.5 | -2.9 | -2.5 | -2.3 |

| POT | -9.9 | -8.6 | -6.4 | -5.3 | -4.7 |

| Ireland | 0.5 | 1.8 | 1.9 | 1.4 | 1.5 |

| Greece | -10.5 | -8.4 | -6.7 | -6.0 | -5.3 |

| Spain | -4.6 | -3.8 | -3.1 | -2.8 | -2.5 |

| EMDE | 1.9 | 2.4 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 1.9 |

| Brazil | -2.3 | -2.3 | -2.5 | -2.9 | -3.1 |

| Russia | 4.8 | 5.5 | 3.5 | 2.2 | 0.8 |

| India | -2.6 | -2.2 | -2.2 | -1.9 | -2.0 |

| China | 5.2 | 5.2 | 5.6 | 6.2 | 6.7 |

Notes; DE: Germany; EMDE: Emerging and Developing Economies (150 countries)

Source: IMF World Economic Outlook databank http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2011/02/weodata/index.aspx

IB Global Rebalancing. The G7 meeting in Washington on Apr 21 2006 of finance ministers and heads of central bank governors of the G7 established the “doctrine of shared responsibility” (G7 2006Apr):

“We, Ministers and Governors, reviewed a strategy for addressing global imbalances. We recognized that global imbalances are the product of a wide array of macroeconomic and microeconomic forces throughout the world economy that affect public and private sector saving and investment decisions. We reaffirmed our view that the adjustment of global imbalances:

- Is shared responsibility and requires participation by all regions in this global process;

- Will importantly entail the medium-term evolution of private saving and investment across countries as well as counterpart shifts in global capital flows; and

- Is best accomplished in a way that maximizes sustained growth, which requires strengthening policies and removing distortions to the adjustment process.

In this light, we reaffirmed our commitment to take vigorous action to address imbalances. We agreed that progress has been, and is being, made. The policies listed below not only would be helpful in addressing imbalances, but are more generally important to foster economic growth.

- In the United States, further action is needed to boost national saving by continuing fiscal consolidation, addressing entitlement spending, and raising private saving.

- In Europe, further action is needed to implement structural reforms for labor market, product, and services market flexibility, and to encourage domestic demand led growth.

- In Japan, further action is needed to ensure the recovery with fiscal soundness and long-term growth through structural reforms.

Others will play a critical role as part of the multilateral adjustment process.

- In emerging Asia, particularly China, greater flexibility in exchange rates is critical to allow necessary appreciations, as is strengthening domestic demand, lessening reliance on export-led growth strategies, and actions to strengthen financial sectors.

- In oil-producing countries, accelerated investment in capacity, increased economic diversification, enhanced exchange rate flexibility in some cases.

- Other current account surplus countries should encourage domestic consumption and investment, increase micro-economic flexibility and improve investment climates.

We recognized the important contribution that the IMF can make to multilateral surveillance.”

The concern at that time was that fiscal and current account global imbalances could result in disorderly correction with sharp devaluation of the dollar after an increase in premiums on yields of US Treasury debt (see Pelaez and Pelaez, The Global Recession Risk (2007)). The IMF was entrusted with monitoring and coordinating action to resolve global imbalances. The G7 was eventually broadened to the formal G20 in the effort to coordinate policies of countries with external surpluses and deficits.

The database of the WEO (http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2011/02/weodata/index.aspx) is used to contract Table 7 with fiscal and current account imbalances projected for 2011 and 2015. The WEO finds the need to rebalance external and domestic demand (IMF 2011WEOSep xvii):

“Progress on this front has become even more important to sustain global growth. Some emerging market economies are contributing more domestic demand than is desirable (for example, several economies in Latin America); others are not contributing enough (for example, key economies in emerging Asia). The first set needs to restrain strong domestic demand by considerably reducing structural fiscal deficits and, in some cases, by further removing monetary accommodation. The second set of economies needs significant currency appreciation alongside structural reforms to reduce high surpluses of savings over investment. Such policies would help improve their resilience to shocks originating in the advanced economies as well as their medium-term growth potential.”

Table 7, Fiscal Deficit, Current Account Deficit and Government Debt as % of GDP and 2011 Dollar GDP

| GDP 2011 | FD | CAD | Debt | FD%GDP | CAD%GDP | Debt | |

| US | 15065 | -7.9 | -3.1 | 72.6 | -3.1 | -2.2 | 86.7 |

| Japan | 5855 | -8.9 | 2.5 | 130.5 | -8.4 | 2.4 | 160.0 |

| UK | 2481 | -5.7 | -2.7 | 72.9 | 0.4 | -0.9 | 75.2 |

| Euro | 13355 | -1.5 | 0.1 | 68.6 | 1.5 | 0.5 | 69.3 |

| Ger | 3629 | 0.4 | 5.0 | 56.9 | 2.1 | 4.7 | 55.3 |

| France | 2808 | -3.4 | -2.7 | 80.9 | -2.5 | 0.6 | 83.9 |

| Italy | 2246 | 0.5 | -3.5 | 100.4 | 4.5 | -2.0 | 96.7 |

| Can | 1759 | -3.7 | -3.3 | 34.9 | 0.3 | -2.6 | 35.1 |

| China | 6988 | -1.6 | 5.2 | 22.2 | 0.1 | 7.0 | 12.9 |

| Brazil | 2518 | 3.2 | -2.3 | 38.6 | 2.9 | -3.2 | 34.1 |

Note: GER = Germany; Can = Canada; FD = fiscal deficit; CAD = current account deficit

FD is primary except total for China; Debt is net except gross for China

Source: http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2011/02/weodata/index.aspx

The conventional approach of the doctrine of shared responsibility consisted of the following policies (Pelaez and Pelaez, The Global Recession Risk (2007), 220-1):

· Devaluation of the dollar relative to European and Asian currencies to eliminate the external imbalance of the US

· Fiscal consolidation in the US to reduce demand relative to output (which actually occurred through the global recession with the current account deficit falling from 6.1 percent of GDP in 2006 (Pelaez and Pelaez, Globalization and the State, Vol. II (2008b), 183) to 3.2 percent currently)

· Increase in demand relative to output in Germany and Japan to reduce their trade surpluses

· Revaluation of Asian currencies relative to the dollar, in particular the Chinese renminbi, to reduce the surplus in current account corresponding to reduction of the current account deficit of the US

There are four important lags in implementing this set of policies (Pelaez and Pelaez, The Global Recession Risk (2007), 220-1) similar to those in economic policy (Friedman 1952):

1. Recognition of the need for policy. That need was recognized in 2006 but it may prove even more difficult within the broader G20

2. Beginning of coordination agreement. Coordination never went beyond research and monitoring in the first attempt

3. Actual policy measures. After intense diplomatic efforts there is a lag of implementation of policies

4. Effects of policies. Assuming adequate and effectively implemented policies with full coordination of member countries, there is still the lag between actual policies and their effect

There are tough differences of interests among the members of the G20. As Olson (1965) analyzed, collective action by groups runs into problems of free riders. Members of a group do not assume their share of actions in the belief that their share of adjustment will be assumed by other members, thus free riding on the agreed policy. Agreements within international forums are similar to soft law in that they are not binding. There are additional technical hurdles in the form of models to determine the doses of policy required in attaining desired adjustment but simulation models may be inadequate because of the Lucas (1976) critique. An added problem is that widespread knowledge of the policy may trigger reversal actions by member countries, creating a temporal consistency problem (Kydland and Prescott 1977). One example in this case would be rush to protectionist policies and undervaluation of currencies.

Cooperation among countries is difficult during periods of prosperity. Joan Robinson (1947) analyzes how much tougher is cooperation during economic stress. The International Monetary and Financial Committee of the IMF reiterated the need for cooperation in ensuring global economic and financial recovery (IMFC 2011Sep24):

“The advanced economies are at the core of an effective resolution of current global stresses. The strategy is to restore sustainable public finances while ensuring continued economic recovery. Taking into account different national circumstances, advanced economies will adopt policies to build confidence and support growth, and implement clear, credible and specific measures to achieve fiscal consolidation. Euro-area countries will do whatever is necessary to resolve the euro-area sovereign debt crisis and ensure the financial stability of the euro area as a whole and its member states. This includes implementing the euro-area Leaders’ decision of July 21 to increase the flexibility of the European Financial Stability Facility, maximizing its impact, and improve euro-area crisis management and governance. Advanced economies will ensure that banks have strong capital positions and access to adequate funding; maintain accommodative monetary policies as long as this is consistent with price stability, bearing in mind international spillovers; revive weak housing markets and repair household balance sheets; and undertake structural reforms to boost jobs and the medium-term growth potential of their economies.

Emerging market and developing economies, which have displayed remarkable stability and growth, are also key to an effective global response. The strategy is to adjust macro-economic policies, where needed, to rebuild policy buffers, contain overheating and enhance our resilience in the face of volatile capital flows. Surplus economies will continue to implement structural reforms to strengthen domestic demand, supported by continued efforts that achieve greater exchange rate flexibility, thereby contributing to global demand and the rebalancing of growth. Fostering inclusive growth and creating jobs are priorities for all of us.”

The WEO finds need of another internal rebalancing of demand from fiscal policy to private demand (2011WEOSep, xvi):

“Policymakers in crisis-hit economies must resist the temptation to rely mainly on accommodative monetary policy to mend balance sheets and accelerate repair and reform of the financial sector. Fiscal policy must navigate between the twin perils of losing credibility and undercutting recovery. Fiscal adjustment has already started, and progress has been significant in many economies. Strengthening medium-term fiscal plans and implementing entitlement reforms are critical to ensuring credibility and fiscal sustainability and to creating policy room to support balance sheet repair, growth, and job creation.”

The Economic Counsellor of the IMF, Olivier Blanchard (2011WEOSep), proposes policies for adjustment of the current threat of combination of global growth slowdown and world financial turbulence. (1) There must be balance between need for continuing short-term fiscal impulses in some advanced countries and credible fiscal consolidation in the medium term. (2) Banks must be recapitalized to withstand the shocks of uncertainty in an environment of growth standstill. (3) Full recovery requires external rebalancing as discussed above.

II World Financial Turbulence. The Economic Counsellor of the IMF, Olivier Blanchard (2011WEOSep, xiii-xiv) identifies two critical risks to the world economy and international finance:

“Low underlying growth and fiscal and financial linkages may well feed back on each other, and this is where the risks are. Low growth makes it more difficult to achieve debt sustainability and leads markets to worry even more about fiscal stability. Low growth also leads to more nonperforming loans and weakens banks. Front-loaded fiscal consolidation in turn may lead to even lower growth. Weak banks and tight bank lending may have the same effect. Weak banks and the potential need for more capital lead to more worry about fiscal stability. Downside risks are very real.”

This blog has been considering systematically world financial turbulence and economic slowdown together with other risks to the international financial system and world economy. This section considers world financial turbulence and section IV World Economic Slowdown the almost nil rate of growth of the world economy. In addition, section III Global Inflation considers inflation that could pose risks of stagflation as during the Great Inflation and Unemployment of the 1970s. The first subsection IIA Collapse of Valuations of Risk Financial Assets considers the drop in valuations of key risk financial assets and subsection IIB Markets Not Dancing Twist “let’s twist again” monetary policy.

IIA Collapse of Valuations of Risk Financial Assets. The past three months have been characterized by financial turbulence, attaining unusual magnitude in the past month. Table 8, updated with every comment in this blog, provides beginning values on Sep 16 and daily values throughout the week ending on Fr Sep 23 of several financial assets. Section V Valuation of Risk Financial Assets provides a set of more complete values. All data are for New York time at 5 PM. The first column provides the value on Fri Sep 16 and the percentage change in that prior week below the label of the financial risk asset. The first five asset rows provide five key exchange rates versus the dollar and the percentage cumulative appreciation (positive change or no sign) or depreciation (negative change or negative sign). Positive changes constitute appreciation of the relevant exchange rate and negative changes depreciation. Financial turbulence has been dominated by reactions to the new program for Greece (see section IB in http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/07/debt-and-financial-risk-aversion-and.html), doubts on the larger countries in the euro zone with sovereign risks such as Spain and Italy, the growth standstill recession and long-term unsustainable government debt in the US, worldwide deceleration of economic growth and continuing inflation. The dollar/euro rate is quoted as number of US dollars USD per one euro EUR, USD 1.3790/EUR in the first row, first column in the block for currencies in Table 8 for Fri Sep 16, appreciating to USD 1.3696/EUR on Mon Sep 9, or by 0.7 percent. Table 8 defines a country’s exchange rate as number of units of domestic currency per unit of foreign currency. USD/EUR would be the definition of the exchange rate of the US and the inverse [1/(USD/EUR)] is the definition in this convention of the rate of exchange of the euro zone, EUR/USD. A convention is required to maintain consistency in characterizing movements of the exchange rate in Table 8 as appreciation and depreciation. The first row for each of the currencies shows the exchange rate at 5 PM New York time, such as USD 1.3696/EUR on Sep 19; the second row provides the cumulative percentage appreciation or depreciation of the exchange rate from the rate on the last business day of the prior week, in this case Fri Sep 16, to the last business day of the current week, in this case Fri Sep 23, such as appreciation of 2.1 percent for the dollar to USD 1.3505/EUR by Sep 23; and the third row provides the percentage change from the prior business day to the current business day. For example, the USD appreciated (negative sign) by 2.1 percent from the rate of USD 1.3790/EUR on Fri Sep 16 to the rate of USD 1.3505 on Fri Sep 23 {[1.3505/1.3790 – 1]100 = 2.1%} and depreciated by 0.2 percent from the rate of USD 1.3473 on Thu Sep 22 to USD 1.3505/EUR on Fri Sep 23 {[1.3505/1.3473 -1]100 = -0.2%}. The dollar appreciated during the week because fewer dollars, $1.3505, were required to buy one euro on Fri Sep 23 than $1.3790 required to buy one euro on Fri Sep16. The appreciated of the dollar in the week was caused by risk aversion with risk financial investments being sold in exchange for dollar-denominated assets.

Table 8, Weekly Financial Risk Assets Sep 19 to Sep 23, 2011

| Fr Sep 16 | M 19 | Tu 20 | W 22 | Th 22 | Fr 23 |

| USD/ 1.3790 -0.9% | 1.3696 0.7% 0.7% | 1.3682 0.8% 0.1% | 1.3571 1.6% 0.8% | 1.3473 2.3% 0.7% | 1.3505 2.1% -0.2% |

| JPY/ 76.76 1.1% | 76.5473 0.3% 0.3% | 76.4020 0.5% 0.2% | 76.7148 0.1% -0.4% | 76.2380 0.7% 0.6% | 76.59 0.2% -0.5% |

| CHF/ 0.875 0.9% | 0.8814 -0.7% -0.7% | 0.8886 -1.6% -0.8% | 0.8993 -2.8% -1.2% | 0.9075 -3.7% -0.9% | 0.903 -3.2% 0.5% |

| CHF/EUR -0.1% | 1.2072 0.1% 0.1% | 1.2158 -0.6% -0.7% | 1.2203 -0.9% -0.4% | 1.2227 -1.1% -0.2 | 1.2229 -1.2% 0.0% |

| USD/ 1.0360 0.9653 -1.1% | 1.0223 0.9782 -1.3% -1.3% | 1.026 0.9747 0.9% 0.4% | 1.004 0.996 -3.2% -2.2% | 0.9755 1.0251 -6.2% -2.9% | 0.978 1.0225 -5.9% 0.3% |

| 10 Year 2.053 | 1.95 | 1.93 | 1.861 | 1.725 | 1.826 |

| 2 Year T Note | 0.15 | 0.16 | 0.19 | 0.194 | 0.219 |

| Year German Bond 2Y 0.51 10Y 1.86 | 2Y 0.46 10Y 1.80 | 2Y0.46 10Y 1.79 | 2Y 0.44 10Y 1.77 | 2Y 0.40 10Y 1.67 | 2Y 0.39 10Y 1.75 |

| DJIA 11509.09 4.7% | -0.9% -0.9% | -0.9% 0.1% | -3.3% -2.5% | -6.7% -3.5% | -6.4% 0.4% |

| DJ Global 1840.92 3.1% | -1.9% -1.9% | -1.7% 0.3% | -3.7% -2.0% | -8.1% -4.7% | -7.6% 0.6% |

| DJ Asia Pacific 1241.18 -0.4% | -1.4% -1.4% | -2.0% -0.7% | -2.0% 0.0% | -5.9% -3.9% | -7.0% -1.2% |

| Nikkei 1.4% | 0.0% 0.0% | -1.6% -1.6% | -1.4% 0.2% | -3.4% -2.1% | 0.0% 0.0% |

| Shanghai 2482.34 -0.6% | -1.8% -1.8% | -1.4% 0.4% | 1.2% 2.7% | -1.6% -2.8% | -1.9% -0.4% |

| DAX 7.4% | -2.8% -2.8% | 0.0% 2.9% | -2.5% -2.5% | -7.3 -4.9% | -6.8% 0.6% |

| DJ UBS Comm. 157.480 -1.9 | -1.8% -1.8% | -1.4% 0.3% | -2.2% -0.8% | -6.5% -4.4% | -9.1 -2.8% |

| WTI $ B 0.7% | 85.890 -2.2% -2.2% | 86.370 -1.7% 0.6% | 84.740 -3.5% -1.9% | 80.33-8.6% -5.2% | 80.22 -8.7% -0.1% |

| Brent $/B 111.98 -0.6% | 109.25 -2.4% -2.4% | 110.23 -1.6% 0.9% | 109.19 -3.5% -0.9% | 105.12 -6.1% -3.7% | 103.96 -7.2% -1.1% |

| Gold $/OZ 1812.1 -2.6% | 1780.0 -1.8% -1.8% | 1807.30 -0.3% 1.5% | 1783.70 -1.6% -1.3% | 1742.20 -3.9% -2.3% | 1625.6 -10.3% -6.7 |

Note: USD: US dollar; JPY: Japanese Yen; CHF: Swiss

Franc; AUD: Australian dollar; Comm.: commodities; B: barrels; OZ: ounce

Sources:

http://www.bloomberg.com/markets/

http://professional.wsj.com/mdc/page/marketsdata.html?mod=WSJ_hps_marketdata

There was flight from risk exposures to safe havens during the week of Sep 23. Risk aversion is present in the appreciation of the USD by 2.1 percent and the continuing strength of the Japanese yen. Exchange rate controls by the Swiss National Bank (SNB) fixing the rate at a minimum of CHF 1.20/EUR (http://www.snb.ch/en/mmr/reference/pre_20110906/source/pre_20110906.en.pdf) prevented flight of capital into the Swiss franc. The week was filled with rumors of further measures by the SNB. Another symptom of risk aversion is the depreciation of the Australian dollar by 5.9 percent in unwinding carry trades.

Risk aversion is also captured by the collapse of the yield of the 10-year Treasury note to 1.725 percent on Sep 22 and 1.826 percent on Sep 23. During the financial panic of Sep 2008, funds moved away from risk exposures to government securities. A similar risk aversion phenomenon occurred in Europe with the collapse of the yield of the 10-year government bond to 1.75 percent.

Equity indexes collapsed during the week. There were heavy losses in the week in major indexes: minus 6.4 percent for DJIA, minus 7.6 percent for DJ Global, minus 7.0 percent for DJ Asia Pacific and minus 6.8 percent for DAX.

Commodities also suffered heavy losses. The DJ UBS Commodity Index lost 9.1 percent in the week. WTI lost 8.7 percent and Brent dropped 7.2 percent. Not even the alleged hedge property of gold survived, declining by 10.3 percent.

There are three factors dominating valuations of risk financial assets that are systematically discussed in this blog.

1. Euro zone survival risk. The fundamental issue of sovereign risks in the euro zone is whether the group of countries with euro as common currency and unified monetary policy through the European Central Bank will (i) continue to exist; (ii) downsize to a limited number of countries with the same currency; or (iii) revert to the prior system of individual national currencies. This issue is discussed in the following subsection IIA1 Euro Zone Survival Risk.

2. United States Growth, Employment and Fiscal Soundness. Recent posts of this blog analyze the mediocre rate of growth of the US in contrast with V-shaped recovery in all expansions following recessions since World War II, deterioration of social and economic indicators, unemployment and underemployment of 30 million, decline of yearly hiring by 17 million, falling real wages and unsustainable central government or Treasury debt (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/09/collapse-of-household-income-and-wealth.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/09/global-growth-standstill-recession.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/08/united-states-gdp-growth-standstill.html).

3. World Economic Slowdown. Careful, detailed analysis of the slowdown of the world economy is provided in Section IV World Economic Slowdown. Data and analysis are provided for regions and countries that jointly account for about three quarters of world output.

There were three interrelated risk waves affecting valuations of risk financial assets: doubts on banks, Greece’s likelihood of default and the European sovereign debt resolution mechanism, currently European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF) (http://www.efsf.europa.eu/about/index.htm) changing to European Stability Mechanism (ESM) in 2013.

First, banks. Moody’s Investors Service (2011Sep23) downgraded by two notches the long-term deposit and senior debt ratings of eight Greek banks. On Sep 21, Moody’s downgraded the long-term and short-term debt of two of the largest US banks (Moody’s 2011Sep21BAC, 2011Sep21WFC) and downgraded the short-term debt of another of the largest banks in the US (Moody’s 2011Sep21C). The rationale for the downgrades is that in there is decreasing probability that banks would be supported by the US government if needed. Brooke Masters, Peggy Hollinger and Alex Barker, writing on Sep 22 on “EU set to speed recapitalization of 16 banks,” published in the Financial Times (http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/49d6240e-e527-11e0-bdb8-00144feabdc0.html#axzz1YQzd3mPK), analyze the move by the European Union to recapitalize 16 banks that came close to failing the stress test conducted during the summer of 2011. Nine banks that failed the test were required to increase capital before the end of the year. The minimum score for passing was 5 percent core tier one capital ratios. The 16 banks scored between 5 and 6 and need to increase their core capital. The IMF (2011GRSRSep, 16) summarizes the banking problems of the euro area:

“The high-spread euro area bank credit default swaps have widened by around 400 basis points since January 2010, in line with the increase in sovereign credit default swap spreads. At the same time, the equity market capitalization of EU banks has declined by more than 40 percent. These market pressures have intensified in recent weeks.”

The change in market capitalization of euro area banks since Jan 2010 is about €400 billion or a loss of 42 percent. The IMF (2011GFSRSep, 21) estimates spillovers of European bank exposures to Greek sovereign debt close to €60 billion. Adding exposures to Ireland and Portugal increases the spillover to €80 billion. The addition of credit risks resulting from Belgium, Italy and Spain raises the total to €200 billion. Declines in asset prices of banks raises total spillover to €300 billion. Precise measurements are quite difficult but the IMF finds the risks to be quite real. There are also exposures of European banks and financial institutions to banks and financial institutions in other areas.

Second, Greece. The week was filled with doubts and reassurances about the program of rescue of Greece. The yield of the 2-year sovereign bond of Greece traded above 50 percent during the week. Default by Greece is viewed by some as extending to other sovereigns in Europe.

Third, European sovereign debt resolution. On Sep 19, Standard & Poor’s lowered the long- and short-term sovereign rating of Italy from A+/Negative/A-1+ to A/Negative/A-1 (S&P 2011Sep19). There are four factors used by S&P for this downgrade: (1) real and nominal slow growth perspective; (2) political obstacles to approving and implementing reforms to promote economic growth; (3) high levels of gross and net government debt; and (4) fiscal program with low commitment to reducing expenditures. In the view of S&P, the greatest weight in the downgrade is given to (2), political obstacles to required reforms, and (3), high debt levels. Bloomberg revealed access to internal working documents showing more drastic measures to contain the sovereign debt crisis. Rebecca Christie and James G. Neuger, writing on Sep 23 on “EU plans Greek buyback program open to all debt,” published by Bloomberg (http://www.bloomberg.com/news/print/2011-09-23/eu-plans-greek-buyback-program-open-to-all-debt-all-investors-for-bailout.html), provide information in a European Union internal document that the second bailout of Greek debt could cover all debt and would be implemented together with the bond swap with private creditors. The EFSF would provide the funds for the buyback. James G. Neuger, writing on Sep 23 on “Europe may speed permanent fund enactment,” published by Bloomberg (http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2011-09-23/europe-weighs-speedier-enactment-of-permanent-rescue-fund-to-stem-crisis.html), informs that an internal working paper of the European Union explores acceleration of the creation of the permanent rescue fund of sovereign debts, European Stability Mechanism (ESM). The resources of the fund would amount to €500 billion or around USD 677 billion that could be sufficient to assist larger countries such as Italy.

IIA1 Euro Zone Survival Risk. The Wriston “doctrine” on sovereign lending was predicated on the argument that countries do not bankrupt (Wriston 1982). Another Wriston idea was that the old Citibank should be more valuable dead than alive: if Citibank followed the model of the old Merrill Lynch and sold the individual components or franchises the value would be higher than that of the unbroken Citibank. There was a rise in leveraged buy outs (LBO) in the 1980s that has been extensively analyzed in academic literature (see Pelaez and Pelaez, Regulation of Banks and Finance (2009b), 159-66). The debt crisis of the 1980s and many other episodes in history actually proved that a country can bankrupt and that many countries can bankrupt simultaneously.

Welfare economics considers the desirability of alternative states, which in this case would be evaluating the “value” of Germany (1) within and (2) outside the euro zone. Is the sum of the wealth of euro zone countries outside of the euro zone higher than the wealth of these countries maintaining the euro zone? On the choice of indicator of welfare, Hicks (1975, 324) argues:

“Partly as a result of the Keynesian revolution, but more (perhaps) because of statistical labours that were initially quite independent of it, the Social Product has now come right back into its old place. Modern economics—especially modern applied economics—is centered upon the Social Product, the Wealth of Nations, as it was in the days of Smith and Ricardo, but as it was not in the time that came between. So if modern theory is to be effective, if it is to deal with the questions which we in our time want to have answered, the size and growth of the Social Product are among the chief things with which it must concern itself. It is of course the objective Social Product on which attention must be fixed. We have indexes of production; we do not have—it is clear we cannot have—an Index of Welfare.”

If the burden of the debt of the euro zone falls on Germany and France or only on Germany, is the wealth of Germany and France or only Germany higher after breakup of the euro zone or if maintaining the euro zone? In practice, political realities will determine the decision through elections.

The euro zone faces a critical survival risk because several of its members may default on their sovereign obligations if not bailed out by a few of the other members. Contrary to the Wriston doctrine, investing in sovereign obligations is a credit decision. The value of a bond today is equal to the discounted value of future obligations of interest and principal until maturity. On Sep 23, the yield of the 2-year bond of the government of Greece was quoted at over 56 percent and the 10-year bond yield traded at over 22 percent. In contrast, the 2-year US Treasury note traded at 0.219 percent and the 10-year at 1.826 percent while the comparable 2-year government bond of Germany traded at 0.39 percent and the 10-year government bond of Germany traded at 1.75 percent (see Table 8). There is no need for sovereign ratings: the perceptions of investors are of relatively higher probability of default by Greece, defying Wriston (1982), and nil probability of default of the US Treasury and the German government. The essence of the sovereign credit decision is whether the sovereign will be able to finance new debt and refinance existing debt without interrupting service of interest and principal. Prices of sovereign bonds incorporate multiple anticipations such as inflation and liquidity premiums of long-term relative to short-term debt but also risk premiums on whether the sovereign’s debt can be managed as it increases without bound.

Much of the analysis and concern over the euro zone centers on the default risk of the debt of a few countries while there is little if any risk of default of the debt of the euro zone as a whole. In practice, there is convergence in valuations and concerns toward the fact that there may not be survival of the euro zone as a whole. The fluctuations of financial risk assets of members of the euro zone move together with risk aversion toward the countries with nil default probability. This movement raises the need to consider analytically sovereign debt valuation of the euro zone as a whole in the essential analysis of whether the single-currency will (or should) survive without major changes.

The prospects of survival of the euro zone are dire. Table 9 is constructed with IMF World Economic Outlook database released during the week for GDP in USD billions, primary net lending/borrowing as percent of GDP and general government debt as percent of GDP for selected regions and countries in 2010.

Table 9, World and Selected Regional and Country GDP and Fiscal Situation

| GDP 2010 | Primary Net Lending Borrowing | General Government Net Debt | |

| World | 62,911.2 | ||

| Euro Zone | 12,167.8 | -3.6 | 65.9 |

| Portugal | 229.2 | -6.3 | 88.7 |

| Ireland | 206.9 | -28.9 | 78.0 |

| Greece | 305.4 | -4.9 | 142.8 |

| Spain | 1,409.9 | -7.8 | 48.8 |

| Major Advanced Economies G7 | 31,716.9 | -6.5 | 76.5 |

| United States | 14,526.6 | -8.4 | 68.3 |

| UK | 2,250.2 | -7.7 | 67.7 |

| Germany | 3,286.5 | -1.2 | 57.6 |

| France | 2,562.7 | -4.9 | 76.5 |

| Japan | 5,458.8 | -8.1 | 117.2 |

| Canada | 1,577.0 | -4.9 | 32.2 |

| Italy | 2,055.1 | -0.3 | 99.4 |

| China | 5,878.3 | -2.3 | 33.8* |

| Cyprus | 23.2 | -5.3 | 61.6 |

*Gross Debt

Source: http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2011/01/weodata/index.aspx

The data in Table 9 are used for some very simple calculations in Table 10. The column “Net Debt USD Billions” in Table 10 is generated by applying the percentage in Table 9 column “General Government Net Debt % GDP 2010” to the column “GDP USD Billions.” The total debt of France and Germany in 2010 is $3853.5 billion, as shown in row “B+C” in column “Net Debt USD Billions” The sum of the debt of Italy, Spain, Portugal, Greece and Ireland is $3531.6 billion. There is some simple “unpleasant bond arithmetic” in the two final columns of Table 10. Suppose the entire debt burdens of the five countries with probability of default were to be guaranteed by France and Germany, which de facto would be required by continuing the euro zone. The sum of the total debt of these five countries and the debt of France and Germany is shown in column “Debt as % of Germany plus France GDP” to reach $7385.1 billion, which would be equivalent to 126.3 percent of their combined GDP in 2010. Under this arrangement the entire debt of the euro zone including debt of France and Germany would not have nil probability of default. The final column provides “Debt as % of Germany GDP” that would exceed 224 percent if including debt of France and 165 percent of German GDP if excluding French debt. The unpleasant bond arithmetic illustrates that there is a limit as to how far Germany and France can go in bailing out the countries with unsustainable sovereign debt without incurring severe pains of their own. A central bank is not typically engaged in direct credit because of remembrance of inflation and abuse in the past. There is a limit also to operations of the European Central Bank in doubtful credit obligations. Wriston (1982) would prove to be wrong again that countries do not bankrupt but would have a consolation prize that similar to LBOs the sum of the individual values of euro zone members outside the current agreement exceeds the value of the whole. Internal rescues of French and German banks may be less costly than bailing out other euro zone countries so that they do not default on French and German banks.

Table 10, Guarantees of Debt of Sovereigns in Euro Area as Percent of GDP of Germany and France, USD Billions and %

| Net Debt USD Billions | Debt as % of Germany Plus France GDP | Debt as % of Germany GDP | |

| A Euro Area | 8,018.6 | ||

| B Germany | 1,893.0 | $7385.1 as % of $3286.5 =224.7% $5424.6 as % of $3286.5 =165.1% | |

| C France | 1,960.5 | ||

| B+C | 3,853.5 | GDP $5849.2 Total Debt $7385.1 Debt/GDP: 126.3% | |

| D Italy | 2,042.8 | ||

| E Spain | 688.0 | ||

| F Portugal | 203.3 | ||

| G Greece | 436.1 | ||

| H Ireland | 161.4 | ||

| Subtotal D+E+F+G+H | 3,531.6 |

Source: calculation with IMF data http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2011/01/weodata/index.aspx

IIB Markets Not Dancing Twist. The term “operation twist” grew out of the dance “twist” popularized by successful musical performer Chubby Chekker (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aWaJ0s0-E1o). Meulendyke (1998, 39) describes the coordination of policy by Treasury and the FOMC in the beginning of the Kennedy administration in 1961:

“In 1961, several developments led the FOMC to abandon its “bills only” restrictions. The new Kennedy administration was concerned about gold outflows and balance of payments deficits and, at the same time, it wanted to encourage a rapid recovery from the recent recession. Higher rates seemed desirable to limit the gold outflows and help the balance of payments, while lower rates were wanted to speed up economic growth.

To deal with these problems simultaneously, the Treasury and the FOMC attempted to encourage lower long-term rates without pushing down short-term rates. The policy was referred to in internal Federal Reserve documents as “operation nudge” and elsewhere as “operation twist.” For a few months, the Treasury engaged in maturity exchanges with trust accounts and concentrated its cash offerings in shorter maturities.

The Federal Reserve participated with some reluctance and skepticism, but it did not see any great danger in experimenting with the new procedure.

It attempted to flatten the yield curve by purchasing Treasury notes and bonds while selling short-term Treasury securities. The domestic portfolio grew by $1.7 billion over the course of 1961. Note and bond holdings increased by a substantial $8.8 billion, while certificate of indebtedness holdings fell by almost $7.4 billion (Table 2). The extent to which these actions changed the yield curve or modified investment decisions is a source of dispute, although the predominant view is that the impact on yields was minimal. The Federal Reserve continued to buy coupon issues thereafter, but its efforts were not very aggressive. Reference to the efforts disappeared once short-term rates rose in 1963. The Treasury did not press for continued Fed purchases of long-term debt. Indeed, in the second half of the decade, the Treasury faced an unwanted shortening of its portfolio. Bonds could not carry a coupon with a rate above 4 1/4 percent, and market rates persistently exceeded that level. Notes—which were not subject to interest rate restrictions—had a maximum maturity of five years; it was extended to seven years in 1967.”

As widely anticipated by markets, perhaps intentionally, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) decided at its meeting on Sep 21 that it was again “twisting time:”

“Information received since the Federal Open Market Committee met in August indicates that economic growth remains slow. Recent indicators point to continuing weakness in overall labor market conditions, and the unemployment rate remains elevated. Household spending has been increasing at only a modest pace in recent months despite some recovery in sales of motor vehicles as supply-chain disruptions eased. Investment in nonresidential structures is still weak, and the housing sector remains depressed. However, business investment in equipment and software continues to expand. Inflation appears to have moderated since earlier in the year as prices of energy and some commodities have declined from their peaks. Longer-term inflation expectations have remained stable.

Consistent with its statutory mandate, the Committee seeks to foster maximum employment and price stability. The Committee continues to expect some pickup in the pace of recovery over coming quarters but anticipates that the unemployment rate will decline only gradually toward levels that the Committee judges to be consistent with its dual mandate. Moreover, there are significant downside risks to the economic outlook, including strains in global financial markets. The Committee also anticipates that inflation will settle, over coming quarters, at levels at or below those consistent with the Committee's dual mandate as the effects of past energy and other commodity price increases dissipate further. However, the Committee will continue to pay close attention to the evolution of inflation and inflation expectations.

To support a stronger economic recovery and to help ensure that inflation, over time, is at levels consistent with the dual mandate, the Committee decided today to extend the average maturity of its holdings of securities. The Committee intends to purchase, by the end of June 2012, $400 billion of Treasury securities with remaining maturities of 6 years to 30 years and to sell an equal amount of Treasury securities with remaining maturities of 3 years or less. This program should put downward pressure on longer-term interest rates and help make broader financial conditions more accommodative. The Committee will regularly review the size and composition of its securities holdings and is prepared to adjust those holdings as appropriate.

To help support conditions in mortgage markets, the Committee will now reinvest principal payments from its holdings of agency debt and agency mortgage-backed securities in agency mortgage-backed securities. In addition, the Committee will maintain its existing policy of rolling over maturing Treasury securities at auction.

The Committee also decided to keep the target range for the federal funds rate at 0 to 1/4 percent and currently anticipates that economic conditions--including low rates of resource utilization and a subdued outlook for inflation over the medium run--are likely to warrant exceptionally low levels for the federal funds rate at least through mid-2013.

The Committee discussed the range of policy tools available to promote a stronger economic recovery in a context of price stability. It will continue to assess the economic outlook in light of incoming information and is prepared to employ its tools as appropriate.”

The worldwide selloff of risk financial assets that followed this statement was loosely attributed by some as reaction to the phrase “there are significant downside risks to the economic outlook,” with emphasis added here. To be sure, there are differences on the extent of the downside risks. Market participants have been keenly aware since the end of 2010 and beginning of 2011 that the world economy was slowing down. The standstill in the US was more than evident after the release of the first and second estimates of IIQ2011. Real GDP grew at the seasonally-adjusted annual equivalent rate of 0.4 percent in the first quarter of 2011, IQ2011, and at 1.0 percent in IIQ2011. Discounting 0.4 percent to one quarter is 0.1 percent and discounting 1.0 percent is 0.25 percent. Real GDP growth in the first half of the 2011 accumulated to 0.35 percent (1.001 x 1.0025), which is equal to 0.7 percent (compounding 1.0035 for two successive half years). The US economy is close to a standstill. This blog has been tracing stagnation of real disposable income since the beginning of 2011. A host of other high-frequency information confirms that growth in the US and worldwide is at standstill. Smart money did not flee from exposures in risk financial assets because of the change in outlook of the FOMC, which is at the frontier of knowledge but about equal to that of market participants. Foresight at the FOMC and at smart money managers is equally cloudy. The global selloff is more likely the consequence of realization that unconventional monetary policy of zero interest rates and various versions of quantitative easing is not effective in recovering the economy.

There are two main issues with “let’s twist again” monetary policy and quantitative easing in general.

First, impact on Treasury yields. The limited size of operation twist is related to the findings of Modigliani and Sutch (1966, 196) that:

“1. The expectation model can account remarkably well for the relation between short- and long-term rates in the United States. Furthermore, the prevailing expectations of long-term rates involve a blending of extrapolation of very recent changes and regression toward a long term normal level.

2. There is no evidence that the maturity structure of the federal debt, or changes in this structure, exert a significant, lasting or transient, influence on the relation between the two rates.

3. The spread between long and short rates in the government market since the inception of Operation Twist was on the average some twelve base points below what one might infer from the pre-Operation Twist relation. This discrepancy seems to be largely attributable to the successive increase in the ceiling rate under Regulation Q which enabled the newly invented CD's to exercise their maximum influence.

4. Any effects, direct or indirect, of Operation Twist in narrowing the spread which further study might establish, are most unlikely to exceed some ten to twenty base points a reduction that can be considered moderate at best.”

Swanson (2011Mar, 31-2) finds with modern state of the art estimation methods operation twist reduced yields of long-term US treasury securities by 15 basis points:

“The present paper has reexamined Operation Twist using a modern high-frequency event-study approach, which avoids the problems with lower-frequency methods discussed above. In contrast to Modigliani and Sutch, we find that Operation Twist had a highly statistically significant impact on longer-term Treasury yields. However, consistent with those authors, we find that the size of the effect was moderate, amounting to about 15 basis points. This estimate is also consistent with the lower end of the range of estimates of Treasury supply effects in the literature.”

The effects of quantitative easing or operation twist of 15 basis points are comparable to those of tightening of the fed funds rate by 100 basis points, as measured by Gürkaynak, Sack and Swanson (2005, 84):

“In particular, we estimate that a 1 percentage point surprise tightening in the federal funds rate leads, on average, to a 4.3 percent decline in the S&P 500 and increases of 49, 28, and 13 bp in two-, five-, and ten-year Treasury yields, respectively.”

There is another operational factors of the “let’s twist again” monetary policy. Swanson (2011Mar) also reminds that lowering long-term yields in a new twist of the yield curve does not require increasing short-term rates as in the part of operation twist policy designed to prevent net capital outflows of the US. The desk of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York can continue to implement the target of fed funds rate of 0 to ¼ percent. This is exactly what the FOMC decided.

Second, impact on other yields, risk aversion and the economy. The crucial issue here is if lowering the yields of long-term Treasury securities would have any impact on investment and consumption or aggregate demand. The decline of long-term yields of Treasury securities would have to cause decline of yields of asset-backed securities used to securitize loans for investment by firms and purchase of durable goods by consumers. The decline in costs of investment and consumption of durable goods would ultimately have to result in higher investment and consumption. It is possible that the decline in yields captured by event studies is ephemeral. The decline in yields just after “let’s twist again” monetary policy this week was caused by the flight out of risk financial assets into Treasury securities, which is the opposite of the desired effect of encouraging risk-taking in asset-backed securities and lending.

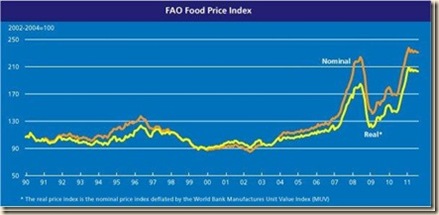

Unconventional monetary policy of near zero interest rates and quantitative easing has been successful mainly in promoting the carry trade from near zero interest rates to leveraged positions in risk financial assets, in particular commodity futures. Chart 1 of the Food and Agriculture Organization shows the Food Price Index that trended down during the recession of 2001. An upward trend was promoted by unconventional monetary policy of 1 percent fed funds rate together with the suspension of the auction of the 30-year Treasury bond to lower mortgage rates, encouraging refinancing that was more important in cash infusion of households than tax rebates. Food prices trended upward and with sharp reductions of monetary policy rates peaked in a big jump to more than $140/barrel in 2008 during a global recession. The flight out of risk financial assets after the announcement of the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) (see Cochrane and Zingales 2009) is shown in Chart 1 in a collapse of the Food Price Index of FAO. With zero interest rates after the FOMC meeting on Dec 16, 2008 (http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/press/monetary/20081216b.htm) and realization in early 2009 that bank assets were not as worrisome as argued for approval of TARP, food prices jumped again to even higher levels.

Chart 1, Food and Agriculture Organization Food Price Index 1990-2011

Chart 1, Food and Agriculture Organization Food Price Index 1990-2011

Source: http://www.fao.org/worldfoodsituation/wfs-home/foodpricesindex/en/

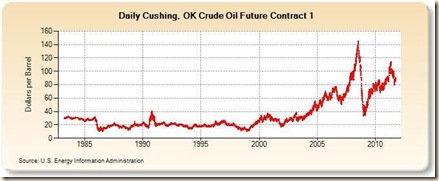

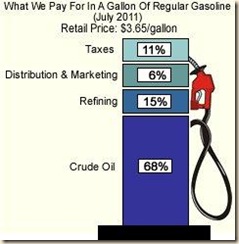

Chart 2 of the US Energy Information Administration shows exactly the same behavior of the price of crude oil. There is the same decline after the 2001 recession that was confused as global deflation. Oil prices trend upward with the near zero interest rates and suspension of the auction of the 30-year Treasury, which was quantitative easing by reduction of supply in a desired segment of the yield curve. There is the same jump of oil prices in 2008 in the midst of sharp global contraction and vertical drop in the flight to safety away from risk financial assets. A new upward trend was promoted by the carry trade from zero interest rates after Dec 16, 2008 (http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/press/monetary/20081216b.htm) and the return of risk appetite in early 2009. Prices have dropped recently because of risk aversion resulting from the European sovereign risk crisis and the US and world growth slowdown. The success of unconventional monetary policy of zero interest rates and quantitative easing is in promoting carry trades from zero interest rates into risk financial assets such as equities, emerging markets, currencies and commodities’ futures.

Chart 2, Crude Oil Cushing, OK, Contract 1

Source: http://www.eia.gov/dnav/pet/hist/LeafHandler.ashx?n=PET&s=RCLC1&f=D

III Global Inflation. There is inflation everywhere in the world economy, with slow growth and persistently high unemployment in advanced economies. Table 11 updated with every post, provides the latest annual data for GDP, consumer price index (CPI) inflation, producer price index (PPI) inflation and unemployment (UNE) for the advanced economies, China and the highly-indebted European countries with sovereign risk issues. The table now includes the Netherlands and Finland that with Germany make up the set of northern countries in the euro zone that hold key votes in the enhancement of the mechanism for solution of the sovereign risk issues (http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/55eaf350-4a8b-11e0-82ab-00144feab49a.html#axzz1G67TzFqs). Newly available data on inflation is considered below in this section. The data in Table 11 for the euro zone and its members is updated from information provided by Eurostat but individual country information is provided in this section as soon as available, following Table 11. Data for other countries in Table 11 is also updated with reports from their statistical agencies. Economic data for major regions and countries is considered in Section IV World Economic Slowdown following individual country and regional data tables.

Table 11, GDP Growth, Inflation and Unemployment in Selected Countries, Percentage Annual Rates

| GDP | CPI | PPI | UNE | |

| US | 2.9 | 3.8 | 6.5 | 9.1 |

| Japan | -1.1 | 0.2 | 2.6 | 4.6 |

| China | 9.6 | 6.2 | 7.3 | |

| UK | 1.8 | 4.5* | 6.1* output | 7.7 |

| Euro Zone | 1.6 | 2.5 | 6.1 | 10.0 |

| Germany | 2.8 | 2.5 | 5.7 | 6.1 |

| France | 1.6 | 2.4 | 6.1 | 9.9 |

| Nether-lands | 1.5 | 2.8 | 8.2 | 4.3 |

| Finland | 2.7 | 3.5 | 7.3 | 7.9 |

| Belgium | 2.5 | 3.4 | 8.4 | 7.5 |

| Portugal | -0.9 | 2.8 | 5.7 | 12.3 |

| Ireland | -1.0 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 14.5 |

| Italy | 0.8 | 2.3 | 4.9 | 8.0 |

| Greece | -4.8 | 1.4 | 8.7 | 15.1 |

| Spain | 0.7 | 2.7 | 7.4 | 21.2 |

Notes: GDP: rate of growth of GDP; CPI: change in consumer price inflation; PPI: producer price inflation; UNE: rate of unemployment; all rates relative to year earlier

*Office for National Statistics

PPI http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/dcp171778_230822.pdf

CPI http://www.statistics.gov.uk/pdfdir/cpi0611.pdf

** Excluding food, beverage, tobacco and petroleum

Source: EUROSTAT; country statistical sources http://www.census.gov/aboutus/stat_int.html